How to Increase Visitor Spending

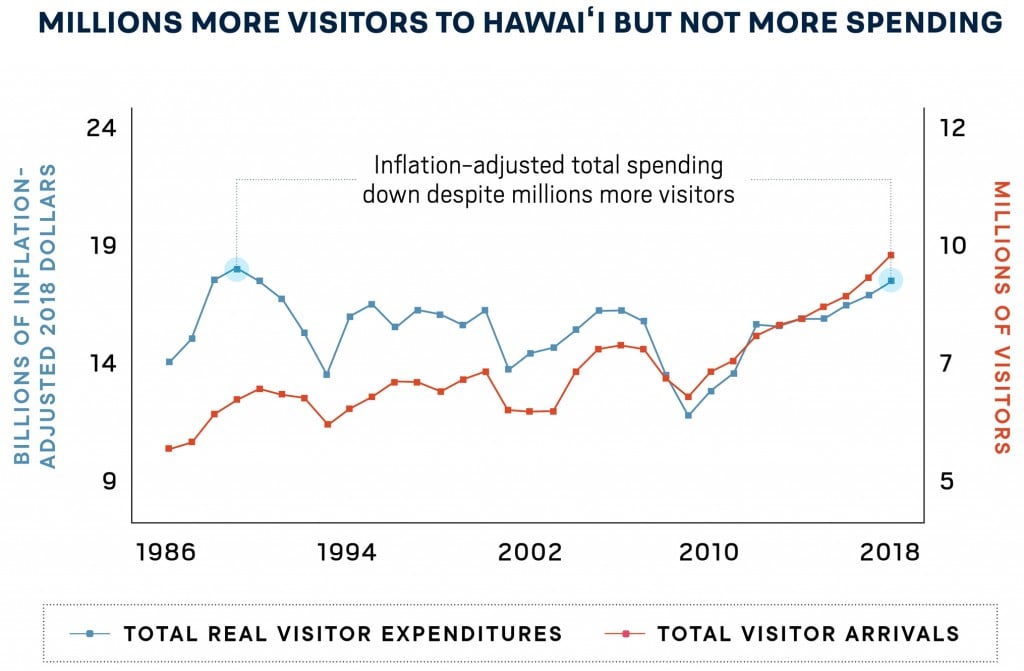

Millions of tourists come to Hawai‘i and venture beyond the resort areas – crowding our parks, beaches, hiking trails, roads and more. But in 2019, total inflation-adjusted visitor spending actually declined, which means there was no extra money to fix this worn infrastructure. Here are three ways to turn that problem around.

Curt Cottrell recalls the tranquility of living next to Maui’s Waiʻānapanapa State Park in 1983.

hat was back when visitors were happy to mostly sit around the hotel pool sipping mai tais and visit a few tourist spots, while locals had places like Wai‘ānapanapa almost all to themselves.

hat was back when visitors were happy to mostly sit around the hotel pool sipping mai tais and visit a few tourist spots, while locals had places like Wai‘ānapanapa almost all to themselves.

“During the day, middle of the week it was empty and silent – and it was beautiful. And all the local people they were hanging out. You have those little fruit stands, you just throw money in a jar and take some bananas,” the state parks administrator says.

“Those days are gone.”

Today, rural Wai‘ānapanapa is a popular stop for tour buses as they traverse the scenic road to Hāna. The park gets so many visitors that its septic tanks overflow and its bathrooms are constantly broken, but the parks division doesn’t have enough money to replace them.

Visitor arrivals are breaking records, but when adjusted for inflation, total visitor spending has declined over the last 30 years. In 2018, 9.8 million people visited the Islands and spent $17.6 billion. In 1989, 6.5 million visitors spent $18 billion in 2018 dollars.

Those extra visitors are wearing down our infrastructure and nature itself, but there’s no extra money for repairs or improvements. Along the way, residents’ attitudes have changed: Today, fewer residents believe tourism brings more benefits than problems, according to the Hawai‘i Tourism Authority’s annual survey. The latest survey also indicates more residents believe tourism is to blame for the high cost of living, damage to the environment and overcrowding.

This story is familiar to Island residents, though the details differ from place to place. Years ago, only locals visited Wai‘ānapanapa Beach on Maui. Now it is so crowded with tourists that the bathrooms frequently break down.

“We’re dealing with all of the catastrophic impacts of tourism but we’re not generating the revenue that we did several years ago when there were less of them,” Cottrell says.

Chris Tatum, president and CEO of the Hawai‘i Tourism Authority, the state agency in charge of supporting tourism, says HTA doesn’t measure success based on the number of visitors. Instead, success is based on visitor satisfaction, resident sentiment, spending per tourist and total visitor spending. Tatum says HTA’s focus is on managing tourism in a way that balances generating tax revenue for the state government while also taking care of Hawai‘i’s communities and natural and cultural resources.

In this article, economists, marketers and other experts in the tourism industry discuss three ways Hawai‘i can increase visitor spending to help offset the impact of swelling visitor arrivals.

TARGET HIGHER-SPENDING VISITORS

Paul Brewbaker of TZ Economics, Frank Haas of Marketing Management and James Mak, a research fellow at UH’s Economic Research Organization, have talked about the contradiction between rising visitor arrivals and flat spending for years.

“In what world is a 40% increase in the number of people crowding the beaches and trails for the same amount of money a good out- come?” Brewbaker asked in an email to Hawaii Business Magazine. In February, the trio published a UHERO paper titled “Charting a New Course for Hawai‘i Tourism,” with the idea of getting tourism stakeholders to talk about solutions that can help the state maintain a high quality of life for residents, quality experiences for visitors and economic contributions from its No. 1 industry. One of those solutions is to focus tourism marketing on attracting higher-spending visitors.

Eric Takahata, managing director of Hawai‘i Tourism Japan, says the push for higher-spending visitors – such as those from Japan – can already be seen, from local hotels upgrading their guest rooms and public areas to Hawai‘i-bound airlines flying larger planes and adding premium-class services. “We’re seeing a conscious shift by all the travel partners to move to a higher-spending visitor, which then equates into higher spending in destination, at the hotels,” he says.

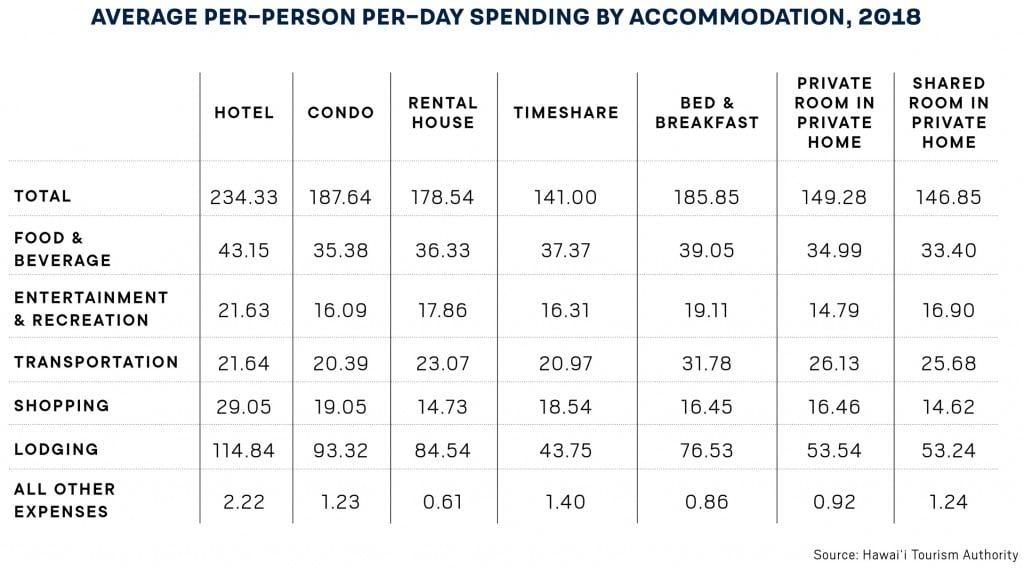

In 2017, Hawai‘i visitors spent an average of $198.50 per day. Visitors who tend to spend more per day include those from Japan and China and people who come for weddings, honeymoons and corporate meetings, says Haas, who is a subcontractor working on HTA’s next strategic plan.

HTA is putting more dollars toward those higher-spending markets, including an additional $1 million this fiscal year toward marketing in Japan. Tatum adds that HTA’s total spending will not change this year – the additional dollars for Japan were taken from other markets – and that some money from marketing was moved to HTA’s community and Hawaiian culture programs to reinvest in the visitor and resident experience.

Haas says overall visitor spending will rise if Hawai‘i can draw more visitors from these higher-spending markets, but that’s tough to do because each segment is fairly small, except the Japanese market. According to HTA’s 2017 Annual Visitor Research Report, visitors who came to Hawai‘i to honeymoon or get married made up 7.3% of visitors who traveled to the state by air. Visitors who came for corporate meetings comprised 0.9% of visitors. If arrivals from those markets are increased by 2% or 5%, he says, that won’t have a huge impact when the overall pie is 10 million visitors: “It’s not a silver bullet.”

Brewbaker, meanwhile, thinks pursuing higher-spending visitors is unlikely to be fruitful. Most visitors have been to the Islands before, and they get smarter about how to save money each time they stay.

“How do we twist the dial, so we get the people we want?” he asks. “My guess is there’s something bigger at work. In my mind, tourists spending less money over time is no different from how we live our lives.”

CHARGE VISITORS FOR USING OPEN-ACCESS RESOURCES

Cottrell points to a calendar on his desk. It’s filled with images of Hawai‘i’s vivid flora, picturesque beaches and lush valleys. Six out of the 12 images are of state parks. What the calendar doesn’t show is “the potholes in the roads, the graffiti and broken bathrooms, the deleterious condition of our workers’ trucks. …We haven’t reinvested in the asset we’re marketing to a level that’s really commensurate to what it needs,” he says.

Take Kalalau Trail on Kaua‘i’s North Shore as an example. The oceanside trail is a global destination yet its composting toilets are so overused they can’t compost waste fast enough. “Our crews are literally shoveling shit into barrels and flying it out and composting it off-site,” says Alan Carpenter, state parks assistant administrator.

Cottrell says the state parks division has never received enough money to effectively manage the large influx of visitors: “Over the span of 20 years, you have two curves going. You have increased use and wear and tear and … decreased capacity of both funding (from the state’s general fund) and staffing.”

Brewbaker says any harm to natural resources from overcrowding is a result of mispricing. If too many people hike a trail or paddle to an island, then the price is too low – and he says a price of zero is certainly too low.

Today’s visitors are different, says Toby Morris, a Kailua resident and founder of Save it for the Keiki, a citizen’s group concerned about tourism management. Instead of staying in resort areas, they’ll venture all over the Islands in search of authentic Hawai‘i experiences. Tourist guides and social media reveal the special spots that were once known only to locals.

One solution is to charge fees to pay for upgrades and maintenance of parks, beaches and trails, though Brewbaker contends this goes beyond raising per-visitor revenue – it’s about stewardship and about having an efficient way to regulate the number of people who are on roads, beaches and trails, and to reduce environmental degradation.

Currently, eight state parks require non residents to pay entry or parking fees, generally $3 or $5 if they drive in. They are Nu‘uanu Pali State Wayside (aka the Pali lookout) and Diamond Head State Monument on Oʻahu, ʻĪao Valley State Monument on Maui, Hāpuna Beach State Recreation Area and ‘Akaka Falls on Hawai‘i Island, and Waimea Canyon, Kōke‘e and Hā‘ena state parks on Kaua‘i. Residents pay only at Diamond Head. Commercial vehicles are charged $6 to $40, depending on the park and number of passengers.

Hanauma Bay on O‘ahu also charges visitors an entry fee, and DLNR’s Nā Ala Hele Trail and Access Program allows a limited number of tour buses to use 28 of its trails and charges each passenger a per-person fee. The state and counties also charge visitor fees for camping, and residents generally pay less or nothing at all.

Several people interviewed for this story think visitors would accept new or increased fees as long as they see the value in paying them. “The idea is no different than when you go to the Mainland and you go to a national park,” Tatum says. “You pay to go in there, but your bathrooms are clean, it’s a safe environment, there are people telling you where to go and what to do. They’re paying for the experience. You have to see the value. … And they like investing in natural resources and community, but you got to price it appropriately.”

Some people, like Sean Dee, executive VP and chief marketing officer for Outrigger Enterprises Group, think visitors are already taxed enough. For example, O‘ahu visitors already pay the 10% transient accommodations tax on lodging and 4.5% general excise tax on everything they buy. However, Dee says, in isolated situations, fees in combination with education and other management efforts could work.

Some examples include Hanauma Bay, which in addition to parking and entry fees, requires visitors to watch a nine-minute education video and shuts down once a week so the fish and bay can rest undisturbed, and Hā‘ena State Park, which limits the number of daily visitors and has required advance reservations since reopening in June after the April 2018 floods. Cottrell says the fees collected at Hā‘ena are meant to be a management tool rather than a revenue generator, but if the model works, it can be used at other state parks that are “being loved to death.”

Carpenter says the existing state park fees are some of the lowest in the nation, and the division needs the additional funding to help protect against unanticipated impacts like Kaua‘i’s floods and Hawai‘i Island’s volcanic activity in 2018 that damaged and closed parks. An estimated $800,000 in camping revenue was lost as a result of the closure of the Kalalau trail and over $100,000 in bus and visitor revenue from the closure of the Pali lookout after a landslide on the Pali Highway. In addition, the division says it has a deferred maintenance backlog and needs more staff to protect resources and public safety.

Diamond Head State Monument charges both residents and nonresidents a walk-in fee of $1. | Photo: David Croxford

Parking and entrance fees make up the biggest chunk of the state parks’ self-generated revenue, Carpenter says. The state parks division didn’t start collecting parking or entry fees for the three Kaua‘i parks until this year. In 2018, the five state parks with parking or entrance fees collected $2.7 million, with Diamond Head alone collecting nearly $1.5 million.

The state parks division plans to pursue a fee increase – an effort that requires changes to its administrative rules. The division is looking to increase fees from $1 for nonresident pedestrians to $5, from $5 for nonresident vehicles to $10; fees would be doubled for commercial vehicles. And it is considering implementing fees at other popular parks.

Cottrell says this additional revenue is needed because the parks serve so many visitors and the division gets a limited share of the hotel room tax. “We have no choice but to extract money from the tourists’ pockets as they enter the park, which is a model that is globally recognized. … The money is just a tool,” he says. “It’s to have better operating capacity to manage parks and cover deferred maintenance.”

DLNR’s Nā Ala Hele program, which manages more than 120 trails statewide, also plans to eventually look at charging fees for its high use trails, says Aaron Lowe, Nā Ala Hele O‘ahu trails specialist. “It’s in the works,” he says. “It’s something on our to-do list.”

ENHANCE THE VISITOR AND RESIDENT EXPERIENCE TO JUSTIFY INCREASED SPENDING AND ATTRACT HIGHER SPENDERS

Kalani Kaʻanāʻanā, Director of Hawaiian Cultural Affairs at HTA, says the visitor experience improves when the state reinvests in its residents, communities and natural and cultural resources. He uses an adaption of the “happy wife, happy life” adage to describe this philosophy: “Happy residents, happy ʻāina. Happy residents, happy visitors.”

HTA is already doing this, Tatum says. In the fiscal year that started July 1, 2019, HTA is putting $20 million toward its cultural, community and natural resources programs.

Several sources agree that Hawai‘i can do a better job of reinvesting in its communities and resources. Erik Kloninger of Kloninger & Sims Consulting, which does research for HTA, says Hawai‘i is the envy of a lot of destinations because it didn’t have to build its attributes. But that bred some complacency that is absent from destinations that have to work harder to build their visitor numbers.

“There was not the will to insist things like our airport should be wonderful. And Honolulu airport is horrible,” he says. “The way that some of the facilities at our beach parks and state parks have been managed is shameful. … I think at a certain point, as a community, we need to say tourism is and will be our No. 1 business – that is our source of income – and we need to do better.”

The grand parade at the Honolulu Festival, which is one of many festivals that HTA supports through its cultural programs. | Photos: Courtesy of Honolulu Festival Foundation; David Croxford

Some organizations have taken it upon themselves to do just that. He cites the Waikīkī Business Improvement District, where hotels and businesses contribute to keeping the area safe, clean and attractive. Privatizing the airport so facilities can be upgraded faster is another example of how to improve the tourism experience, Kloninger adds; but that proposal has repeatedly died at the state Legislature, leaving modernization in the hands of a notoriously slow state decision-making and procurement process.

Enhancing the visitor experience also applies to attractions and accommodations, says Mufi Hannemann, president and CEO of the Hawai‘i Lodging and Tourism Association, especially as Hawai‘i faces increasing competition from sun, sand and surf destinations in Asia, Mexico and Europe.

Outrigger’s Dee agrees, saying that Hawai‘i has to develop globally competitive, best-in-class accommodations. Several hoteliers, including Outrigger, have heavily invested in their accommodations in the last five years. Outrigger says it recently completed a $35 million renovation on all 498 rooms and public spaces at its Beachcomber property on Waikīkī Beach. The company also plans to invest in its other two Hawai‘i Outrigger properties in the coming years.

Alfred Grace, president and CEO of the Polynesian Cultural Center, which averages 2,500 visitors daily, says the state has to keep in mind visitors are evolving. They’re looking for unique experiences off the beaten path – and Hawai‘i has to become an expert in providing them.

Guests learn to make palusami, a traditional Samoan dish, while participating in a hands-on experience at the Polynesian Cultural Center. | Photo: The Polynesian Cultural Center; David Croxford

The Polynesian Cultural Center says that visitors are interested in more hands-on experiences, so this year it started letting a few of them enter the center’s Samoan Village before it opens to the general public to learn how to harvest food, start a fire, cook and eat a meal.

Hawai‘i tourism has done well recently, he says, but people in the tourism industry need to recognize that increasing competition for visitors’ time and money will always be a factor.

“There’s never an opportunity to sit back and relax and enjoy the ride,” he says. “We always have to keep pushing to exceed guest expectations.”