After leaks at the Navy’s Red Hill fuel facility culminated in a water contamination crisis impacting thousands of military families, the U.S. Department of Defense said Monday that it will permanently shut down the World War II-era facility.

The decision marks a reversal from the Pentagon’s previous efforts to keep the underground facility in operation. Secretary of Defense Lloyd Austin is committed to defueling, Pentagon spokesman John Kirby said during a briefing.

“He believes this is the right decision, not just for our national security for a more distributed and dispersed fueling capability through the Indo Pacific but also for the environment and for our gracious host and neighbors in Hawaii, and of course for military families,” Kirby said.

The Red Hill Bulk Fuel Storage Facility was built in the 1940s to serve American military forces during the war. Twenty massive tanks, a system of pipelines and miles of tunnels were constructed in the Halawa mountainside to protect the resource from attack and use the force of gravity to deliver fuel to Pearl Harbor. The facility, made of steel and porous concrete, is located just 100 feet above Oahu’s main drinking water aquifer, and petroleum contamination has been present under the facility for years.

U.S. Rep Kai Kahele, who had introduced legislation to shut down Red Hill, called the Pentagon’s announcement a “much-needed and overdue step.”

“Today is a historic day in Hawaii – it is a day of both relief and celebration,” he said in a statement. “It is proof that when we come together, as a community, change is possible. It is proof that when we come together to work towards a common good, we can make a difference.”

In 2014, an estimated 27,000 gallons of fuel escaped from the tanks, activating concerns from community members and the Honolulu Board of Water Supply. But Navy officials insisted that the facility was safe and didn’t threaten the drinking water.

Those assurances continued throughout last year after two major leaks. In May, a pipeline burst and an estimated 19,000 gallons of jet fuel escaped, according to the Navy. Some of that fuel was allegedly captured in a fire suppression drain line that would itself open up on Nov. 20 in a location very close to the Red Hill drinking well that served the Pearl Harbor area.

The week of Thanksgiving, military families started to smell and taste fuel in their water. Thousands sought medical treatment for illnesses, including some who were hospitalized. The ordeal has upended the lives of those impacted, displacing them from their homes. Many have questioned whether they will ever trust the military again.

In December, the Hawaii Department of Health issued an emergency order demanding that the Navy remove the fuel from Red Hill until it can demonstrate it can operate safely. The military has fought the order, and the U.S. Department of Justice even filed lawsuits in state and federal court against it.

Meanwhile, the Honolulu Board of Water Supply Chief Engineer Ernie Lau, who has expressed his alarm about Red Hill for years and has called for the protection of Oahu’s water resources, has been lauded for his efforts in demanding Red Hill’s closure. In a statement on Monday, he said he was cautiously optimistic about the military’s announcement.

“We cannot let our guard down and we need to continue to protect our precious wai,” he said, using the Hawaiian word for water.

The military’s response to the crisis and its previous insistence on keeping Red Hill open has sparked sustained protests and has turned Red Hill into a hot-button political issue. One advocacy group, the Oahu Water Protectors, said that the military’s news is the culmination of years of political pressure.

“It is also just the beginning of a new stage in what is likely to be a long struggle towards full accountability and remediation,” the group said in a statement. “It could take generations to right what the Navy has wronged. But as long as the U.S. military continues to threaten our water, we will be there to protect it.”

The military plans to provide an action plan for “safe and expeditious defueling of the facility” by May 31, according to Austin’s statement.

As soon as the military has taken “corrective actions” to ensure that defueling can happen safely, it will move to permanently close Red Hill and conduct environmental remediation, the defense secretary said, adding that the actual defueling is expected to take 12 months.

Centrally located fuel storage made sense in the 1940s, and Red Hill has served the armed forces well for decades, Austin said.

“But it makes a lot less sense now,” he said. “The distributed and dynamic nature of our force posture in the Indo-Pacific, the sophisticated threats we face, and the technology available to us demand an equally advanced and resilient fuel capability.”

“Moreover, when we use land for military purposes, at home or abroad, we commit to being good stewards of that resource,” he added. “Closing Red Hill meets that commitment.”

Austin’s statement included a promise that the Honolulu community will have a say in determining the future of Red Hill – a notable pledge given the American military’s history of using and polluting Hawaii’s resources to meet its own ends regardless of community objections.

“When we begin to consider land-use options for the property after the fueling facility is closed, we will stay in lockstep with communities in Hawaii,” he said. “Nothing will be decided without careful and thorough consultation with our partners.”

To the military families whose lives have been deeply disrupted by the contamination, Austin promised a return to normal.

“We owe you the very best health care we can provide, answers to your many questions, and clean, safe drinking water,” he said.

Under pressure, Hawaii’s elected officials who were mum about the facility for years suddenly called for its closure amid the contamination crisis.

U.S. Sen. Mazie K. Hirono, a member of the Senate Armed Services Committee, said she’d been urging the defense department to make this decision for weeks. She said it was “the right thing to do for the people of Hawaii and for our environment.”

The Hawaii Democrat said there is a lot of work to do, including safely defueling the facility and environmental cleanup efforts. Hirono promised to work closely with federal and state officials to ensure this happens.

She said she will also work with the defense department to ensure it has the resources it needs to meet the strategic fuel reserve needs of the Indo-Pacific Region and protect national security.

“The military plays a vital role in Hawaii and it is important we work together going forward,” she said.

Sen. Brian Schatz, a member of the Senate Appropriations Committee, secured $100 million in federal funds last month to defuel Red Hill and introduced legislation in the Senate to permanently shut the facility down.

“In order to implement this decision, we’re going to have to provide additional resources and hold DoD’s feet to the fire through congressional oversight. I will continue to work with our federal and state partners to see this through,” he said in a statement.

Gov. David Ige said in a statement that he looks forward to working with the Navy to close Red Hill.

“This is great news for the people of Hawaii,” he said. “Our national defense begins with the health and safety of our people, and there are better solutions for strategic fueling today than there were when the Red Hill storage facility was built.”

But removing the fuel won’t be without challenges, he said at a press conference. There is not enough capacity in Hawaii to store the over 100 million gallons of fuel sitting in Red Hill tanks.

“Defueling would mean moving the fuel from the storage tanks through pipelines into a shore-based facility and then ultimately into tankers or ships to move the fuel out of state,” Ige said.

The military’s investigation into the cause of the contamination was submitted to the Pentagon in January but has not yet been released to the public.

Red Hill’s eventual closure was welcome news for military families who drank fuel from their taps.

Army Maj. Amanda Feindt, whose family, including her two young children, were sickened by the contamination noted that the Navy had initially denied and downplayed the crisis.

She welcomed the decision, saying it “feels really good to be heard.

“It feels like history is not going to repeat itself anymore,” she said. “It doesn’t undo what has been done. It just feels like there is a light at the end of the tunnel.”

But those feelings are complicated by continued distrust, she said. Feindt’s Ford Island neighborhood was just declared safe by military and health department officials, so they’ve moved back in after weeks in a hotel. But the family still isn’t using the water, she said.

“Of course we want normalcy, but we don’t trust the water in our home,” she said. “We truly are traumatized.”

In an interview, David Kimo Frankel, an attorney for the Sierra Club of Hawaii, said he was puzzled by the military’s assertion that decentralizing its fuel assets is advantageous.

“The Navy has consistently argued the Red Hill facility was necessary and irreplaceable, and all of a sudden it’s not,” he said. “So it’s hard to give anything DOD says any credibility.”

Frankel also questioned the military’s plan. The state’s emergency order required a defueling plan by Feb. 3, he said, but Austin’s statement indicates it won’t be filed until the end of May. Austin also didn’t mention compensation for the local and state government and the Honolulu Board of Water Supply for costs incurred because of the contamiantion.

“It is certainly a step forward when the secretary of defense says they’re going to shut down the Red Hill fuel tanks,” he said. “But there are still lots of reasons for skepticism. Our water is still contaminated.”

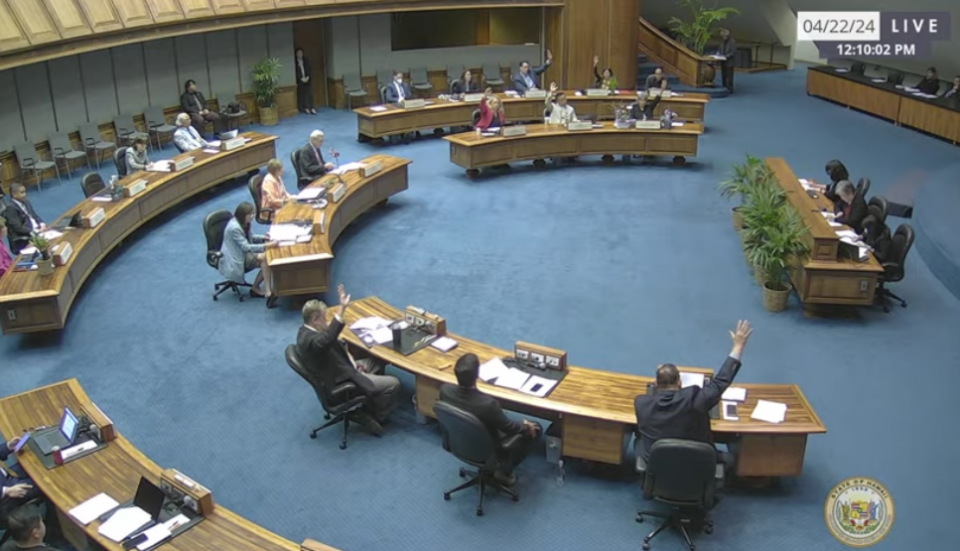

Sen. Glenn Wakai, who represents military communities surrounding Pearl Harbor, has similar reservations. At a press conference on Monday, he pointed to past spills and attempts by the Navy to cover up leaks from the facility.

“You just need to look at the Navy’s track record,” Wakai said. “What’s not to be skeptical about what they’ve done?”

Reporters Blaze Lovell and Joel Lau contributed to this article.

Sign up for our FREE morning newsletter and face each day more informed.

Sign up for our FREE morning newsletter and face each day more informed.

Civil Beat is a small nonprofit newsroom that provides free content with no paywall. That means readership growth alone can’t sustain our journalism.

The truth is that less than 1% of our monthly readers are financial supporters. To remain a viable business model for local news, we need a higher percentage of readers-turned-donors.