Three Ways to Pay Back Nature Before it Forecloses on Hawaiʻi

Imagine going to your favorite Hawai‘i beach, picnicking on the white sand and snorkeling over a reef teeming with yellow tang. Or hiking through a māmane reserve and hearing palila sing. How much should you pay for such experiences?

Most of us assume they should be free. But other people point to the cost of maintaining such resources or the cost of their abuse – a cost that collectively all locals and tourists pay. The problem is we’re not paying enough.

A recent study conducted by Conservation International, a Washington, D.C.-based nonprofit, concluded that our state needs to spend at least $886 million a year to care for our ecosystems and biocultural resources, yet our current conservation spending is $535 million a year.

“In other words, we’re running at a 40% deficit. And it shows,” says Emilia von Saltza, a Hawai‘i-based project manager for Conservation International’s Green Passport initiative.“We are the invasive species capital of the world, requiring us to spend millions annually. Our forests are declining, causing our aquifers to drop. If we don’t manage these forests and the waters they capture, we’ll have to put millions into transport pipes and desalination plants.

“Despite the fact that visitors rank nature and ocean their top reasons for coming, we put less than 1% of our total state budget into maintaining these assets,” says von Saltza, who is the author of a 2019 report sponsored by Conservation International called “Green Passport: Innovative Financing Solutions for Conservation in Hawai‘i.”

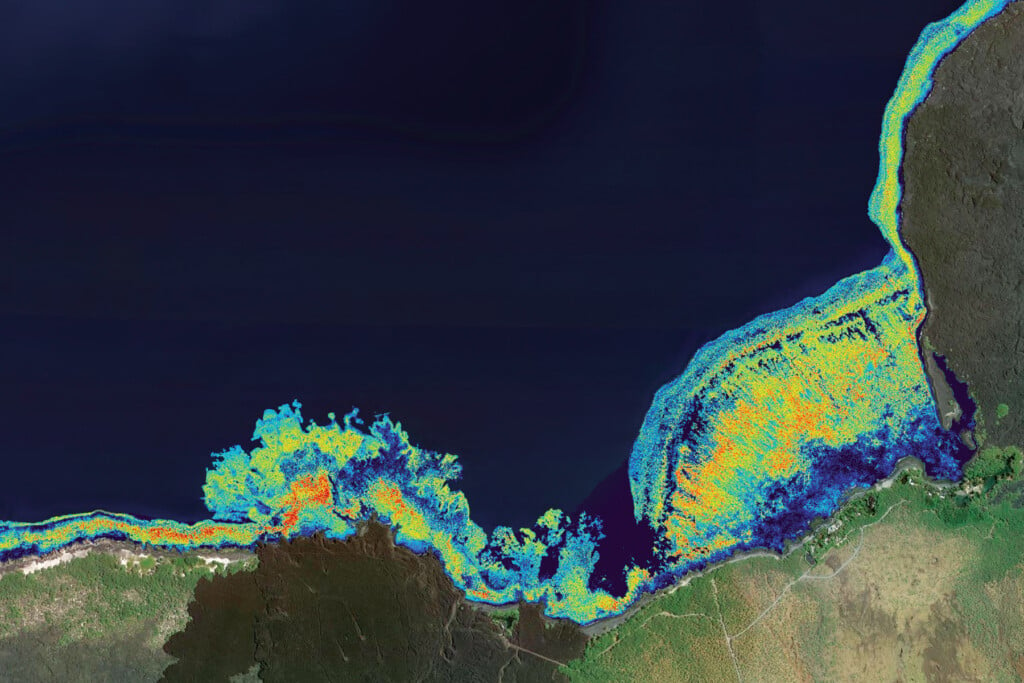

Assigning dollar values to nature may seem odd. Nonetheless, there are increasing attempts to do just that so we can understand what its degradation or loss means to our economy. For example, every year reefs provide a value of close to $400 million by protecting coastal structures on O‘ahu and $50.7 million by protecting the coastlines of Hawai‘i Island, according to a study conducted by the U.S. Geological Survey, the Nature Conservancy and UC Santa Cruz. Just think about where our tourism economy would be without the hotels that line our coasts.

As we continue to burn the fossil fuels that cause global warming, we increase the conservation costs of both the natural world and the human-made one. The Hawai‘i Sea Level Rise Vulnerability and Adaptation Report from 2017 estimates the loss of structures and land due to flooding will cost over $19 billion. Another measure, called the Social Cost of Carbon, quantifies the long-term damage caused by carbon emissions. By some estimates, Hawai‘i’s SCC is at least $155 for every metric ton of carbon we emit, totaling over $2 billion a year just for O‘ahu.

“Our lack of support of the environment is the biggest unfunded liability the state faces, even bigger than health care,” says Eric Co, senior program officer for ocean resiliency at the Harold K.L. Castle Foundation. “Our environment is so much of our economy and yet we invest so little in it. We’ve been deppreciating these capital assets for so long. Now we’ve got to invest back in them.”

Traditional forms of conservation funding are not enough, despite a committed philanthropic community, says John Leong, the president and CEO of Pono Pacific Land Management LLC. “Grant funding runs out and government budgets change and are not always reliable. And the challenge is that natural resources always have a constant need and there’s always more human pressures put on the environment,” he says.

Hawai‘i’s leaders are investigating various strategies beyond traditional conservation funding. For example, the Sustainability Business Forum, a group of 19 local businesses and nonprofits, are collaborating on initiatives to increase climate resiliency through partnerships across sectors.

This story examines three proposed initiatives – green fees, carbon offsetting and carbon taxes – and considers the opportunities and challenges each presents in confronting Hawai‘i’s unfunded nature liability.

• • •

Green Fees

When Jennifer Koskelin-Gibbons was growing up, she visited Ngchus Beach to camp, picnic and snorkel in the deep turquoise water. For many Palauans like her, it was a place to make family memories. But the increase in tourists threatened to change all that.

“One of the things we started to see with the development of the tourism sector was that first-time travelers coming to Palau didn’t know what to do in the space. They often thought it was a park or zoo where you come in and touch everything,” says Koskelin-Gibbons, co-founder of the Palau Legacy Project and Palau Pledge.

In response, Palau instituted a Pristine Paradise Environmental Fee of $100 in 2018. This fee, which is included in all international airline tickets to Palau, is expected to generate about $10 million a year.

Fourteen other destinations, including the Galapagos, New Zealand, the Maldives, Cancun and Venice, also have visitor green fee programs, which vary from $1 a night to a $100 entrance fee. Some, like Palau’s, are nationwide programs; others, like Cancun’s, are more targeted and could serve as models for Hawai‘i, according to the Green Passport report sponsored by Conservation International.

While the details differ, they share a common purpose: to collect revenue from tourism and put it toward environmental conservation. In part due to such revenue sources, Palau’s investment in its natural environment is $92 per tourist, New Zealand’s is $188 and the Galapagos’ is $373.

Hawai‘i’s is just $9, according to the Green Passport report.

“We did an analysis of the geographies that Hawai‘i competes with for visitors, and we see that we’re underinvesting by a factor of 10. What we are spending per visitor is extremely low” in comparison, says Jack Kittinger, Conservation International global fisheries and aquaculture program senior director, based on O‘ahu. “And that’s incredible considering that people come here because of our nature and ocean.”

Aerial view of Koror in Palau. Tourists flock to the famous Rock Islands to snorkel. | Photo: Getty Images

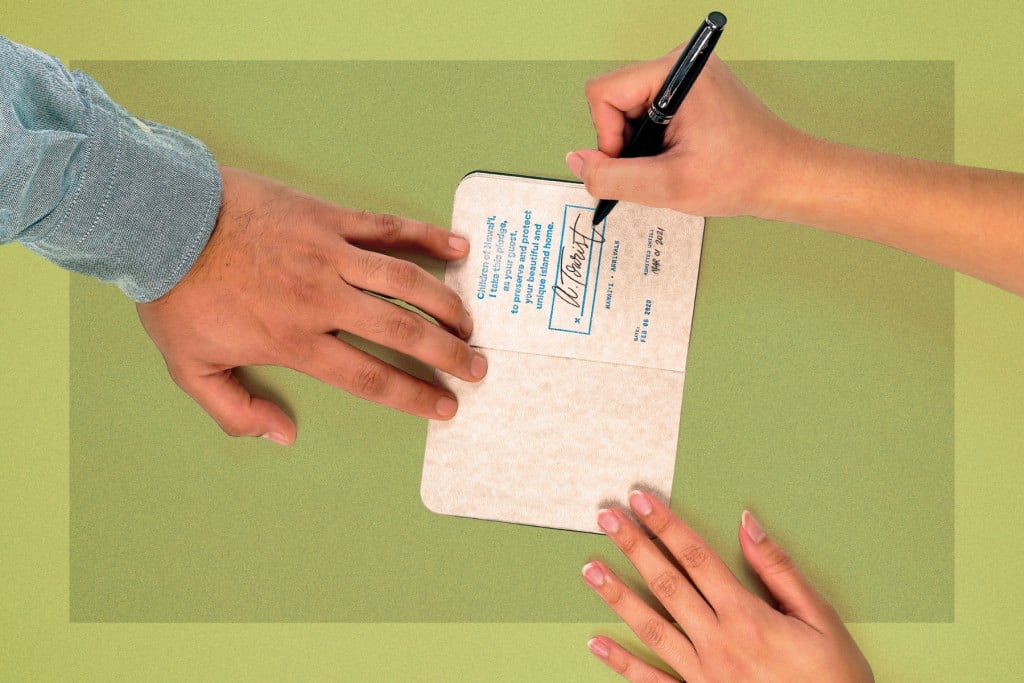

For Koskelin-Gibbons, raising awareness is just as important as the fees. To foster that awareness, each visitor is required to read and sign a pledge to respect the environment and culture of Palau.

“One of the important things that the pledge does is support the expectation that it’s more than just about collecting fees. We also need good actors. The fee is to support Palau and its protected areas and marine sanctuary. But at the same time, we can’t do it ourselves. We need the help of our visitors to be mindful of the fragile nature of coral and fisheries, and in particular to be respectful of the culture,” Koskelin-Gibbons says.

This increased awareness has also put pressure on local companies to change their ways. To help visitors identify the products and services that embody the conservation values that are consistent with the pledge, Palau is developing a certification program for businesses.

“Visitors now expect conservation-mindedness from all of us. When it’s not there they experience a disconnect. So we have to be proactive. Doing the right thing isn’t just a thankless activity. It’s smart business,” says Koskelin-Gibbons.

Data from the Galapagos show that its $100 entrance fee has not affected arrival rates, according to the Green Passport report. In fact, the majority of those visitors surveyed support an even higher fee.

What’s most important is that people understand where their money is going, says Pablo Obregon, Conservation International senior program manager of fisheries, based in Arlington, Virginia.

“It’s important to be transparent and participatory. Make sure to clearly describe the rationale and justify everything. Is the objective to raise money to support management of places that are being degraded? Is it to manage places that are overcapacity? Is this just to fund conservation in Honolulu? So long as you have well-thought-out objectives, everything flows down from there,” says Obregon, who also worked as an advisor for the rezoning of the Galapagos Marine Reserve.

Many people worry that additional fees or taxes on tourists will harm the state’s biggest industry. According to the Hawai‘i Tourism Authority, Hawai‘i received almost 10 million visitors, who supported over 200,000 jobs and generated over $17 billion in spending and over $2 billion in tax revenue in 2018. (2019 numbers were not available at publication time.)

“This is an industry that doesn’t want to put more fees on clients, and for good reason,” says Kittinger. “Our approach has been to learn and empathize with the sector and try to design the initiative so that it improves the visitor experience and is a benefit to the tourism sector.”

He says that despite the challenges, he is encouraged that the green fee idea keeps bubbling up. “This idea started a few years ago. We formed a working group, but thought it was a ‘moonshot.’ With guidance from the Hawai‘i Leadership Forum, we started to poke at it again. Now, it has moved from wild moonshot to maybe this is possible if we apply some effort, so let’s see how it’s worked in other places.

“Every time we tried to kill this, saying it wouldn’t work, it came alive again.”

• • •

Carbon Offsets

Koa, the largest native tree in our state, means “warrior” in Hawaiian. It is one of the most expensive woods in the world, prized for its depth, color and texture. Used to make canoes, medicine and red dye, it is also an integral part of traditional culture.

Now, this warrior will soon find itself in another important role as the star player in an 8,000-acre carbon offset project in the Kona Hema forest on Hawai‘i Island. Developed by The Nature Conservancy, with investment from members of the Sustainability Business Forum, the project is expected to provide 120,000 credits over its first 10 years. Two other carbon offset projects, both on DLNR land, will follow: one on Maui at the Kahikinui Forest Reserve and Nakula Natural Area Reserve and the other in Hawai‘i Island’s Pu‘u Mali Forest on the north slope of Mauna Kea.

“For the first time, all emitters, including businesses and individuals, will be able to compensate for their carbon footprint by buying offset credits from our own native koa,” says Mark Fox, former director of external affairs at The Nature Conservancy.

“You can go online anytime and buy offset credits, but right now it would be from places outside of Hawai‘i. Sure, it doesn’t matter in the sense that the atmosphere doesn’t care. But it matters to our Hawai‘i businesses. They want to offset their emissions here,” says Fox, adding that people can begin buying these credits in late 2020.

The Green Passport is not a passport like the one you use for international travel. But it is both the name of an October 2019 report prepared for Conservation International and a symbol of the idea that preserving nature has a cost that locals and visitors must pay so future generations can also enjoy it.

Visitors increasingly expect this as well. For example, in 2016 organizers of a major international conservation conference in Hawai‘i ended up purchasing credits from Peru and India, according to the Sustainability Business Forum. Leong, the Pono Pacific president and CEO, says other big groups, including movie production teams, have also been disappointed to hear they can’t offset in Hawai‘i.

“We have users from across the world coming to our state, and it’s important to have very easy ways to give back. If we aren’t finding those easy ways, we’re losing out on opportunities to steward our resources. Having carbon offsets provides direct ways for locals and tourists to tangibly make a difference. But it also creates a third leg besides government and grants to capture that revenue for Hawai‘i that we wouldn’t have otherwise,” says Leong, whose company is helping develop the Pu‘u Mali Forest carbon offset program.

That revenue includes offsets from one of the state’s largest entities, Hawaiian Airlines, No. 3 on Hawaii Business Magazine’s Top 250 list of the state’s biggest companies. As a party to a voluntary United Nations plan encouraging sustainability within aviation, Hawaiian Airlines will cap its emissions, offsetting any amount it exceeds.

“It is in our interest to find ways that we can offset our carbon right here in Hawai‘i. We want to see ways that these huge tracts of land here can be put to this kind of use,” says Ann Botticelli, Hawaiian Airlines’ senior VP for corporate communications and public affairs.

“This is important to us because we’re Hawai‘i’s airline and 88% of our employees live in this archipelago. It’s in our interest to make sure that this place is protected.”

While anyone with access to land can plant trees to offset their own emissions, selling offset credits on the global market requires a certification process.

“The challenge is in proving how much carbon is actually being captured by the trees and guaranteeing that it will remain sequestered for a long time,” says Julius Lorenz Fischer, Hawai‘i Green Growth project coordinator.

“The certifiers go through … academic publications on koa growth rates and they decide whether there’s enough data” to know how fast the koa is growing and how much carbon it’s sequestering, Fischer says. “That has to do with nitty-gritty factors like the density of carbon in the trunk or the way it might grow differently in a natural forest versus a reforested area.”

Because each of the three offset projects being developed in Hawai‘i is unique, working in tandem is important, says Irene Sprecher, forestry program manager at the DLNR’s Division of Forestry and Wildlife.

“The Kona Hema project is focused on improved forest management, which means they are committed to maintaining all that carbon that’s already being sequestered there. Those trees are already mature and can store more carbon because they are bigger. They’ll be able to sell more offsets at the beginning of their project. The Maui project, on the other hand, is a reforestation project. Our trees will grow slowly at first and start capturing more carbon over a period of time,” says Sprecher.

Pūlama Lāna‘i COO Kurt Matsumoto sees the possibility of converting land on Lāna‘i into an offset project as a fitting way to renaturalize parts of an island that humans have transformed.

Cattle ranching was introduced to the island in the 1800s, which led to the forest being decimated, he says. “What followed ranching was pineapple. It was a monocrop culture covering a huge amount of land which was once all forest. But there’s been no pineapple now for nearly three decades. And we’ve seen this on other islands – once the plantation is gone, the land goes fallow.

“Carbon credits make a lot of sense because you’re not just trying to create another industry, you’re helping the environment. It would provide a great legacy for generations to come,” says Matsumoto.

Some, however, caution against thinking of offsetting as a way to pay our way out of the climate change crisis. “This may seem convenient because you don’t necessarily have to change your behavior. You can keep sinning while you pay some money. But the actual problem is sinning,” says Josh Stanbro, chief resilience officer and executive director of Honolulu’s Office of Climate Change, Sustainability and Resiliency.

“There’s definitely room for carbon sequestration, but let’s remember that it doesn’t address the disease, just the symptoms. This is not a get out of jail pass. We still need to get off of fossil fuels.”

• • •

Carbon Tax

In 2018, Yale professor William Nordhaus won the Nobel Prize in economics for research on carbon taxes, or fees imposed on the burning of carbon-based fuels. He showed that higher prices encourage businesses and consumers to find alternatives to carbon-based energy, spurring innovations that make those substitutes competitive. Consequently, he argued, carbon taxes are the most effective and efficient way to lower emissions.

Not everyone is convinced.

“Part of the controversy has to do with the idea of a tax,” says Makena Coffman, UH Mānoa Institute for Sustainability and Resilience director and a professor of urban and regional planning.

“Here in Hawai‘i we have policy to become carbon neutral (in electricity) by 2045. But that transition is not without cost. Everything we are doing has an implicit tax. It’s already going into people’s rates. And there’s no way we can do this that doesn’t cost us anything. But the problem is that the carbon tax makes those costs explicit. When you call something out, that’s when people get worked up about it,” says Coffman.

“So while a carbon tax is considered a first best policy, it creates a weird dilemma. Is it better to know or not know what we are going to pay?” Coffman adds.

Hawai‘i does, in essence, already have a de facto fossil fuel tax. It started off as a so-called barrel tax on petroleum products, excluding aviation fuel, and now includes coal and gas. The problem, however, is that these rates have not been high enough to incentivize change, says Jeff Mikulina, executive director of Blue Planet Foundation, a local nonprofit that advocates for reduced carbon emissions.

“It ends up being about 2.5 cents per gallon. It’s a wash, just a rounding error. It doesn’t serve the purpose of a carbon tax, which is to dissuade people from buying fossil fuel,” says Mikulina.

In addition, there is frustration among advocates for more conservation funding that the revenue from the current fossil fuel tax is not being used as originally intended. Of the $25 million that it generates annually, only 43% goes to programs related to the environment, while the balance is sent to the state’s general fund.

“That’s a bone of contention. The money goes to good projects but there’s not a real strategy for how that funding gets used,” says state Rep. Nicole Lowen, chair of the House Energy and Environmental Protection Committee.

Legislation proposes to pay for a carbon tax study so Hawai‘i can better understand how it might change the tax to persuade more people to reduce their use of carbon. HB1584 passed the House in 2019 and is in the Senate’s hands at the start of the 2020 session. The bill’s goals include examining different pricing options for the tax and projecting how much revenue it would raise.

Just as importantly, the study would explore how to implement the tax in an equitable way, says Lowen, who sponsored the bill. “If you’re lower income working in Oceanview and don’t have the option of public transportation to work at the hotel, you’re stuck. The tax shouldn’t disproportionately impact you. We need to make sure we get that right.”

What’s most important, says Coffman, who has been tapped to lead the study if it is approved, is ensuring the tax creates the desired new behaviors and technology innovation. “What we need to understand is how sensitive the different sectors are to changes in prices. We know prices matter and people respond. The question is how much. The devil is in the details of the price rate. If it’s too small, it just won’t be effective.”

There are case studies that may offer useful information. “When the price of oil shot up many years ago, people started to look at hybrid cars and scooters and riding bikes to work – things that make them healthier and save costs. So you have a real-life experiment with what it looks like when you have a price increase,” says Stanbro.

British Columbia has instituted a carbon tax equivalent to about $30 per metric ton. According to the B.C. government, the Canadian province’s real GDP grew by 19% between 2007 and 2016 while its net emissions declined 3.7%. B.C. also provides direct rebate checks to residents from a portion of the carbon tax revenues: 154.50 Canadian dollars per adult and 45.50 per child.

Mikulina believes a reasonable tax for Hawai‘i would be around $50 per metric ton, or $16 per barrel. He says this would cost consumers about 38 cents more per gallon of gas and 3 cents per kilowatt-hour of electricity.

The estimated annual tax revenue would be $500 million. Although the current carbon tax excludes aviation fuel, if we include domestic aviation, says Mikulina, that could add another $160 million in revenue.

As for how that revenue should be used, Mikulina envisions a variety of investments, including incentives for energy efficiency or renewables, clean energy infrastructure, financing to make clean energy improvements more affordable, and rebates to taxpayers, especially lower income ones.

Ultimately, he says, a carbon tax is meant to level the playing field, allowing alternative forms of energy a chance to compete in an ecosystem dominated by big polluters.

“We’ve been letting everyone use the atmosphere as an open sewer,” Mikulina says. “And people are feeling it. Over 200 high temperature records have been broken throughout the state. Trade wind days have been cut in half over the last 40 years. We now need to get the accounting right, so that fossil fuels lose their advantage.”

• • •

4,000 Days

The idea of paying more through fees, offsets or taxes to fund our conservation needs is contentious. Businesses worry about the impact on our economy and our tourism sector. Residents worry about paying even more. But regardless, say several of the people interviewed for this piece, we have to collectively acknowledge the costs of environmental degradation and the risks involved if we don’t deal with them.

“It’s our environment that funds our quality of life and underscores our whole economy. But we need to be clear about the fact that we will be paying for sea level rise. We will be paying for stronger hurricanes. The question is, do we plan for it upfront, or do we roll the dice and see what happens later?” says Mikulina.

For Stanbro, the chief resilience officer, making the costs explicit is critical. In service to that, both the City and County of Honolulu and Maui County are joining more than a dozen other U.S. communities to sue fossil fuel companies for damages stemming from climate change.

“Ever since we started pumping oil, the biggest polluters have been subsidized by inflicting damage somewhere else in the ecosystem. Exxon, Shell, BP, ConocoPhillips – less than 100 companies are responsible for the lion’s share of global damage. That’s why the litigation is important – they made trillions of dollars in profit. Some of that should come back to pay for the damage their product caused.

“We have a decade, about 4,000 days, to fix our climate problem, or we will surpass tipping points that no amount of money or innovation can reverse.”

Emilia von Saltza, Hawai‘i-based project manager, Conservation International’s Green Passport initiative

“And in the meantime, who is paying? Our coral reefs that have not been able to reproduce are paying. Our fish populations are paying. Our oceans are paying. And eventually we will have to pick up the bill when it comes to disaster response or lowered tourism incomes,” says Stanbro.

But we can’t count on lawsuits to pay for all the investment in our environment. Ultimately, in some form, we will need to pay more to maintain our environment. For Stanbro, this requires complete transparency on where our money is going.

“There’s been this assumption that people don’t want to pay. But when they understand that what they are paying for is something they love, they don’t mind. What they do mind is if they pay a fee and it disappears into a black box. When those funds are raided or they are taken and used elsewhere, that’s when they lose faith in the system. Folks are only willing to pay if it’s going into a locked box only for environmental preservation,” says Stanbro.

While there are disagreements over the pros and cons of any new or big approach, advocates of green fees, carbon offsetting and carbon taxes emphasize that the worst thing we can do is wait and see.

“The science on this has never been more clear. We have a decade, about 4,000 days, to fix our climate problem, or we will surpass tipping points that no amount of money or innovation can reverse,” says Saltza, the Conservation International project manager.

“The coming decade will be the most productive of many of our lives.”

Members of the Sustainability Business Forum:

AHL

Alexander & Baldwin

Bank of Hawaii

First Hawaiian Bank

Harold K.L. Castle Foundation

Hawai‘i Community Foundation

Hawai‘i Gas

Hawai‘i Pacific University

Hawaiian Airlines

Hawaiian Electric

Hawaiian Telcom

Kamehameha Schools

Kualoa

The MacNaughton Group

Pineapple Tweed

Pūlama Lāna‘i

Resort Trust

Ulupono Initiative

Zephyr Insurance Company, Inc.