The Cost of Dying

There are many ways to memorialize the dead, but one constant is that a little forethought and communication – before you go – can save your family a lot of money and grief after you’re gone.

A few times a month, Billy Pa helps paddle an outrigger canoe about a quarter mile off Waikiki Beach.

That’s where families and friends say goodbye to loved ones and scatter their ashes. “I think the reason people do it is because they have a love of the ocean,” Pa says.

It’s the general area where the ashes of Duke Kahanamoku, Don Ho and hundreds of other people have been left over the decades. Pa wants his ashes scattered there, too, and so does his wife.

Today, there are many ways to say goodbye to the departed, and lots of families are opting for alternatives to traditional funerals and burials. The reasons vary, including saving money or the environment, and memorializing a person in a unique way that seems appropriate to their lives. One thing that is true about all of these ways: A little planning while you’re still here means fewer costs and less confusion for your family when you’re gone, funeral directors and morticians say.

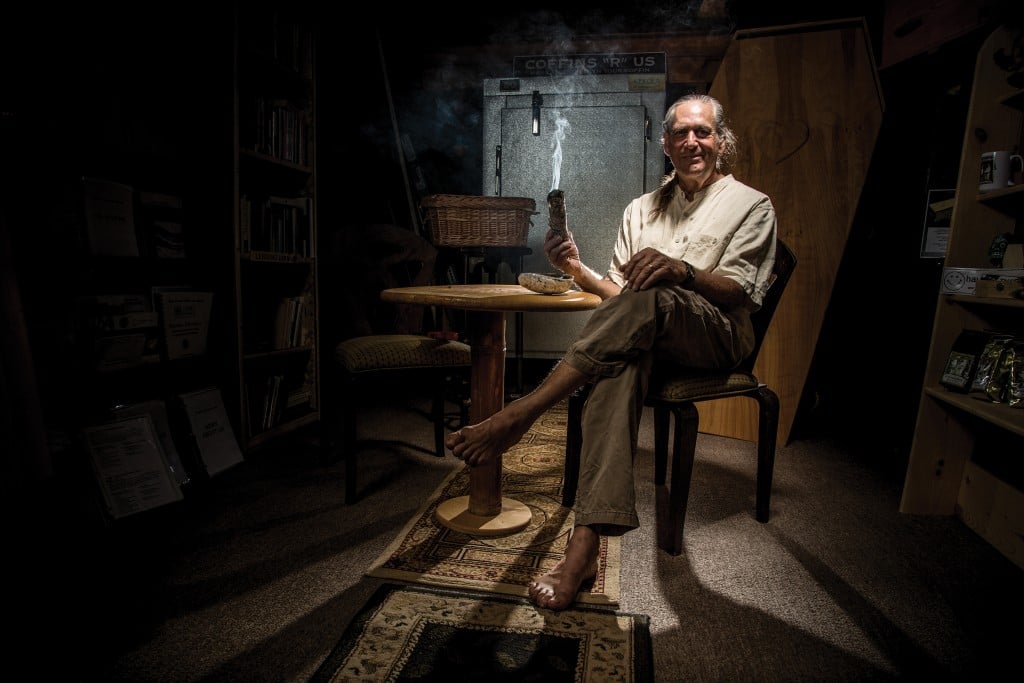

“Most people don’t want to talk about it and certainly don’t want to think about it. But, then, all of a sudden family members are emotional and grieving, and that’s not the right time to make economic decisions,” says Bodhi Be, a founder of the Death Store on Maui, a service of a nonprofit called Doorway Into Light.

CREMATION SAVES MONEY

Pat Newalu, a manager at Borthwick Mortuary, says nearly half of Borthwick’s clients choose traditional funerals with burials, a much higher percentage than at other mortuaries. Photo by Olivier Koning

The cheapest option is cremation, which can start at $775 at a nonprofit provider like Oahu Mortuary. But once families get into traditional funerals and burials, the costs quickly add up, including items such as the casket, flowers, prayer cards and extended ceremonies.

“They start nickel and diming the families,” says Blanca Acevez Eberhardt, funeral services manager at Oahu Mortuary. “The calculator just keeps ticking.”

Sometimes the total cost can soar past $37,000, and that doesn’t necessarily include the burial plot. Some funerals can even reach six figures.

At Oahu Mortuary, funeral services start at the low end of industry standards, around $3,000. But that doesn’t include the burial plot, which runs from $10,000 to $15,000 at Oahu Cemetery in Nuuanu, the oldest public cemetery in the state. Meanwhile, families may choose to pay less than $2,400 for a plot at Homelani Memorial Park in Hilo, one of Hawaii’s cheaper burial options.

At Borthwick Mortuary in Honolulu, the cost of cremation is $3,300. Families must also take into account other details like the cost of transporting the body to the funeral home, which runs about $745 at Borthwick. Additionally, they may opt for a hearse and limousine, costing over $700 each. There’s also other add-ons such as memorial books for $225 and stationary starting at $195.

Families can save money by pre-planning funeral arrangements with mortuaries or purchasing packages, says Pat Newalu, a manager at Borthwick. Nearly half of Borthwick’s clients choose traditional funerals with burials, a much higher percentage than at other mortuaries, she says. And the vast majority of them have already started planning arrangements.

Newalu says Borthwick has been operating for 100 years, and has nurtured relationships with many local families who seek traditional burial services. But the company continues to adapt funeral packages to suit their clients’ changing needs, for instance, by offering packages that include services like catering and floral arrangements.

“I think that we stand behind our services and our products,” Newalu says. “It’s really nice when we’re able to help families.”

Caskets can be costly: Most sold in the state range from $1,900 to $6,000, but some can go much higher; one offered by Ballard Family Moanalua Mortuary is priced at $17,000. Biodegradable caskets made of materials such as pine, wicker and bamboo are cheaper and gaining in popularity.

Only 17 percent of those surveyed nationwide had talked in-depth about their funeral wishes with family or friends, according to a 2015 report from the National Funeral Directors Association. “We don’t see death as part of life, and there are all kinds of issues with that,” says Be of Maui’s Death Store.

The lack of planning places a burden on grief-stricken families, who don’t know what their loved ones wanted, he says.

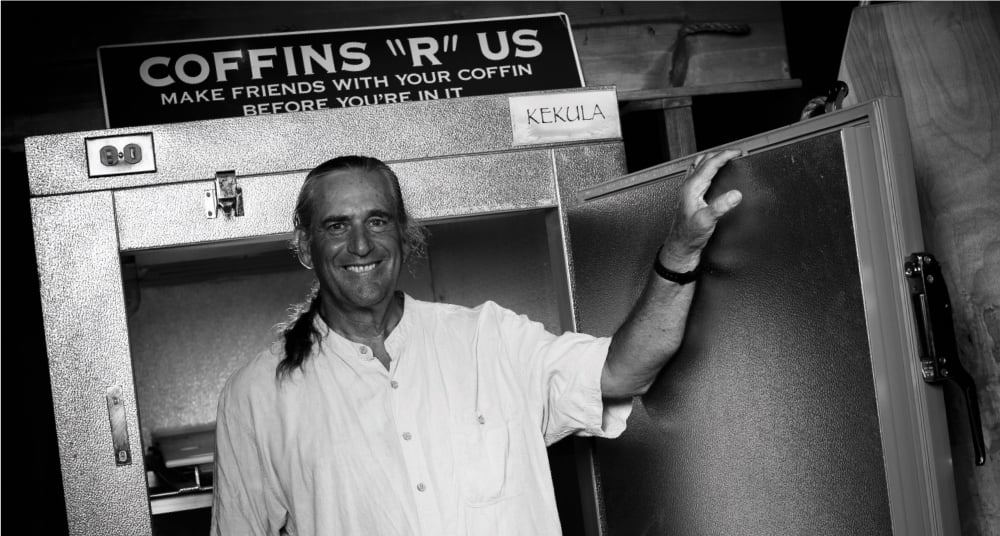

MAUI’S DEATH STORE

Be says he and others opened the Death Store in Haiku, Maui, with the hope of revolutionizing the funeral industry. He says he wants to transform the “business of dying” and re-create it as a “sacred service.”

For instance, he says, the store also holds a monthly bereavement group, and works to start conversations about death and dying before someone passes away. He says he wants to be fully transparent about the funeral process so families can be as engaged as they wish. In fact, they can even help prepare the body if they want, he says.

“I like the family as included as they would like to be. If I had a graveyard, I would let them dig the hole.”

Hospice providers agree that making arrangements as early as possible helps free families to process grief and ensure they’re not spending money unnecessarily.

“There’s a stigma with hospice that it’s for the last few days, and nothing could be farther from the truth,” says Michelle Bowerman, director of business operations at Islands Hospice. “There are so many services that getting on sooner helps the patient, helps the family. Waiting until the very, very last moment isn’t the best idea.”

Hospices can help people with bereavement counseling, funeral planning and difficult decisions such as what to do with the body, she says. Social workers can outline options that you may not have previously considered, such as donating the body to a medical school.

“You have to respect what each person wants. It’s not for us to judge, or for us to change their mind,” Bowerman says.

CHANGING TIMES

Michelle Bowerman, director of business operations at Islands Hospice, says hospices help families in many ways, including with bereavement counseling, funeral planning and difficult decisions, such as what to do with the body. Photo by Olivier Koning

You know the traditional steps. First, a visitation ceremony at the mortuary, followed by a funeral service. Then, the body is taken to the cemetery, where family and friends says a few words before the body is lowered into the ground.

Once, that was what most families expected. Not anymore. Changing attitudes toward religion and environmentally conscious thinking are among the factors driving changes.

For instance, cremation, which is often cheaper than burial, is getting more popular. Hawaii has one of the highest cremation rates in the country with 73 percent of families choosing cremation; nationwide, less than 50 percent do, according to the National Funeral Directors Association. In Hawaii, the number of cremations grew about 10 percent since 2005, and that number is supposed to grow again to 85 percent by 2030, according to the organization.

Some say this trend is largely because of the high cost of burial, which can include fees for the plot, the casket, opening and closing the grave, grave liners and transportation to the cemetery.

At Ballard Family Mortuaries, a traditional funeral service – including the casket – can cost up to $37,000, but that doesn’t include viewing, visitation or any ceremonies at the funeral home. Yet cremation starts at only $700. For an additional $295, families can witness the cremation.

“Our business model has always been built on cremation because we knew that’s where the industry was going,” says Mark Ballard, owner of Ballard Family Mortuaries. “We see a lot of people who are not having a traditional religious funeral service. It’s more of a family kind of service, or no service at all.”

Ballard grew up in Kentucky, where he was introduced to the death care industry at 11 years old. His neighbor owned a funeral home, but the man’s children weren’t interested in the trade. He took Ballard under his wing, and about a decade later, Ballard opened his first funeral home in Kentucky.

Years later, he sold his funeral homes on the Mainland and moved to Maui, where he opened his first Hawaii-based mortuary. When he opened it in the late 1990s, about 60 percent of his families opted for cremation. Now, about 75 percent do, he says.

At Oahu Mortuary, as many as 90 percent of families choose cremation, says Eberhardt.

Afterward, a popular practice is to scatter the ashes at sea, she says.

“Many of the tourists that come to do an ash scattering do it in Waikiki, but the local families go to the smaller beaches,” Acevez says.

In 2008, president-elect Barack Obama said farewell to his grandmother, Madelyn Dunham, by scattering her ashes on the rocky shore near southeast Oahu’s Lanai Lookout – the same place where he scattered his mother’s ashes a decade earlier.

Bodhi Be of the Death Store. Photo by Chris Evans

Only 17 percent of Americans talk in-depth about their funeral wishes with family or friends.

Source: National survey conducted for a 2015 report from the National Funeral Directors Association

GREEN BURIALS ONLY

Lisa Alo sits on a ledge in the floor of the Death Store, facing shelves filled with biodegradable urns. It’s a small, dark space, tucked into the corner of a small shopping center in the lush Haiku area of Maui.

The Maui store only offers “green” burials, selling handmade pine box and wicker caskets, which can be purchased starting at around $500. The store doesn’t use embalming fluid or other toxic chemicals for burials, she says. Scattering of ashes, though, is often more popular than burials among the Death Store’s clients, she says. That’s what she did with her sister’s ashes.

More and more, Alo says, families are choosing to have funerals in their homes. Some consider a mortuary an unnecessary cost and find more closure with a memorial at home.

“It’s not a business, it’s life and death. As much as with birth you need a hospital, you don’t need a mortuary with death,” Alo says.

The nonprofit also caters to an unusual option chosen by a handful of people each year: ocean burial, Alo says. Environmental Protection Agency rules say a body can be buried at sea at least three miles from shore. If using a casket, it can’t be made from plastic. The EPA also recommends that holes be drilled in the container, and that extra weights be added to offset the buoyancy of the body.

Be, one of the Death Store’s founders, says this option would probably be chosen by more people if they knew about it.

“Some people have such a love for the ocean that they’ve either requested or would love to buried in the ocean,” Be said.

Another option is a biodegradable urn that helps birth a tree. It costs around $150.

“Obviously the trend is towards something that environmentally makes sense,” Be says. “No toxic chemicals, no embalming fluids and nothing expensive, yet simple.”

Eventually, Be says, he hopes to create an environmentally friendly burial park. There could be trails, picnic areas and gardens, along with the cemetery, he says.

On the mainland, similar spaces are popping up. For instance, Prairie Creek Conservation Cemetery in Florida goes a step further, ensuring the land is legally protected from future development and non-biodegradable materials. Supporters say these cemeteries are a cheaper option for families that also limit pollution from chemicals such as embalming fluid, while maintaining spaces for plants and wildlife.

Burial at the Florida conservation cemetery costs a one-time fee of $2,000, plus the costs of getting the body to the burial site, says Freddie Johnson, director of the nonprofit Prairie Creek Conservation Cemetery. He says the total cost of the transportation, services and burial usually end up around $4,000.

“Even if our costs were higher, families would generally be saving money by not embalming, not paying for a vault and not paying for a fancy metal casket,” he says.

Plus, some families are able to cut down costs by digging the grave, lowering the body and covering it themselves, he says. Many families often come back to visit the burial site, having picnics in the area, bird-watching or going hiking, he says.

“It’s quite amazing to see how relaxed they get when they’re out in nature, and how healing nature can be,” Johnson says. “And, there’s more involvement from the families, which can often bring healing in itself.”

ASHES AT SEA

For over 25 years, Capt. Ken Middleton has helped families celebrate the lives of the departed, scattering their ashes onto the clear, blue waters surrounding Hawaii.

“We have folks from all around the world,” Middleton says. His company, Hawaii Ash Scatterings, has helped hundreds of families say goodbye to their loved ones by holding memorials in the waves, just offshore of iconic places like Waikiki and Lahaina.

No state approval is needed for Hawaii residents to store or scatter ashes. He says ash scattering is becoming more popular and has mostly remained free from state and county regulation.

The state Health Department doesn’t consider cremated remains a health hazard as long as they are scattered without creating a nuisance.

“It can be on the shoreline; we just ask that they do it discretely,” says June Takushi of the Health Department. “They just have to make sure it’s not over some kind of water reservoir.”

The Hawaii Department of Land and Natural Resources says no permit is required to scatter ashes by land, sea or air, but they can’t be scattered on state or federal property, which includes forest reserves and watersheds. Also, you should get permission from landowners before scattering ashes on private property, the agency says.

However, the agency requires a permit for ash scattering ceremonies at sea that involve large crowds or multiple boats, and that permit needs to be acquired about two weeks before the ceremony. Plus, the DLNR asks that families scatter loose flowers instead of lei, because sea creatures can get sick from eating string.

Past three miles offshore, ash scattering is regulated by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. The agency requires written notification of ash scattering within 30 days of the ceremony, which includes the name of the deceased and the location where the remains were scattered.

The EPA says natural flowers and wreaths can be scattered, but plastic or synthetic flowers aren’t allowed because they don’t easily break down in the ocean.

NO NEXT OF KIN?

John Burns, administrative officer at the Honolulu Medical Examiner’s office, says some people’s bodies remain unclaimed because the next of kin do not wish to claim the body or can’t afford to. Photo by Olivier Koning

That’s Very Sad, But Also Rare.

For Dina Lloyd, dying is a part of daily life.

Until recently, Lloyd was a social worker at Islands Hospice, where she worked with dozens of Hawaii residents who were deemed terminally ill, helping them and their families to decide what happens in the final days and hours, and after they pass away.

For a few, there are no next of kin. Still other patients don’t want their families and friends to know they’re dying. In those cases, no one will grieve. Tearful friends and family will not plan a funeral service. They will not scatter their ashes.

“It’s not always a money thing, so it seems,” Lloyd says. “We’ve had many people who have said, ‘I have these family members, but I haven’t talked to them in 40 years and please don’t call them.’”

In 2015, about 8,000 people died in Honolulu County, according to the county Medical Examiner’s Office, and a tiny percentage went “unclaimed.” Between May 2015 and May 2016, there were 46 bodies in “storage” in Honolulu County, which means the Medical Examiner’s office accepts the remains because there’s nowhere else for them to go, according to their office. The state must approve before they can be buried or cremated.

Of those few, only a small group go truly unidentified, says John Burns, administrative officer at the Honolulu Medical Examiner’s office. After interviewing friends, family and coworkers and searching through medical and dental records, the medical examiner can almost always determine who the deceased is.

“It’s a large community, but it’s a small community in many ways, so you don’t have that kind of a problem,” Burns says.

Some remain unclaimed because the next of kin is on the Mainland or elsewhere, and the survivors do not wish to claim the body or can’t afford to. After all, Hawaii is a mecca for tourists from around the world, and some choose to make a permanent home here. According to U.S. Census data, slightly more than half of people who live in Hawaii – including the military population – were born here.

“The nature of relations here is vague and very inclusive, and so Uncle Joe or Aunt Sue may just be a neighbor they had when they were kids and nothing else.” —John Burns

More often, the deceased has next of kin who are local, but they are unwilling or unable to claim the body. Burns explains: “Most people think that an unclaimed body is one where there is no next of kin. But, remember, next of kin here is a broad concept.

“The nature of relations here is vague and very inclusive, and so Uncle Joe or Aunt Sue may just be a neighbor they had when they were kids and nothing else,” he says. “So it wouldn’t be surprising at all that when presented with a bill for a funeral,” they are reluctant to claim the body.

At Islands Hospice, social workers will provide charity services to ensure no one is turned away in their final days, even if they can’t pay.

“We get folks who can tend to become unclaimed, whether that’s because of financial issues or their home or lack of home situation,” Lloyd says. “We basically just meet people where they’re at, so no matter their circumstances we look at the big picture and figure out what are their needs.”

If someone is unclaimed, the state takes custody. The Hawaii Department of Human Services and counties work together with mortuaries to ensure such bodies are cremated or buried. The department’s MedQuest Division will pay for the burial or cremation of someone whose family cannot afford it. Over 100 bodies were referred to the MedQuest program from the Honolulu Medical Examiner’s Office during a 12-month period in 2015-16, according to the office.

Eberhardt of Oahu Mortuary says her mortuary is one of the few that participates in the program. The mortuary holds onto the ashes, “in case someone comes out of the woodwork years later and wants to claim them,” she says.