“Talent Roadmap” Declares: Now is the Time to Reinvent Hawaiʻi’s Economy

The coronavirus has put tens of thousands of local people out of work.

Enhancing workforce development is the starting point, according to a report from the Hawaiʻi Executive Collaborative, which is based on input from almost 200 people.

The economic impact sends a clear signal: Hawaiʻi needs to build a more resilient economy that can support residents with living-wage jobs. Simply returning to the status quo is not the answer.

That’s the message from a collaboration of public, private and philanthropic leaders. They say Hawaiʻi needs to train people for jobs that will be needed and in demand now and in the future – and that means preparing them for careers in health care, technology and skilled trades. The way to do that, they say, is through more work-based learning, retraining and credentialing programs, and more industry- driven solutions and partnerships.

These priorities are outlined in the Hawaiʻi Executive Collaborative’s report, “From Today to Tomorrow: A Talent Roadmap to Support Economic Recovery in Hawaiʻi,” which was developed with input from nearly 200 people in education, workforce development, community organizations, business and government. The Hawaiʻi Executive Collaborative is a nonprofit that brings together local business, nonprofit and government leaders committed to collectively addressing Hawaiʻi’s challenges.

Micah Kāne, President & CEO, Hawaiʻi Community Foundation and board member of HEC.

“At no point have I seen in the last 25 years a cross-sector effort to try to really diversify our economy and to use our workforce as a means to do it,” says Micah Kāne, president and CEO of Hawaiʻi Community Foundation and a board member of HEC.

This roadmap is meant to provide a common vision that can guide leaders in different sectors, says Terrence George, president and CEO of the Harold K. L. Castle Foundation, which helped pay for the creation of the roadmap. Carrying out its strategies, he says, will require an “unprecedented ability to build our partnership muscle” and expand existing collaborations among high schools, colleges and employers to better align education with in-demand and needed jobs. Today, career academies in public high schools and apprenticeship and credentialing programs in community colleges serve hundreds of people. Tomorrow, they’ll need to serve thousands, George says.

Terrence George, President & CEO, Harold K. L. Castle Foundation

Some of the work to implement this roadmap is already underway and can be seen in the recently launched programs that provide temporary employment and training opportunities to displaced workers, writes Lynelle Marble, executive director of the Hawaiʻi Executive Collaborative, in an email. At the same time, partners involved in the roadmap are working to share its strategies with leaders in the government, nonprofit, philanthropy and business sectors. “Our goal is to utilize the roadmap as a foundation to help align efforts and guide policy so that we can build an economy that will allow all of our residents to thrive,” she writes.

Kāne adds that a cross-sector state leadership team still needs to be created to establish agreed-upon measurable goals and metrics for success. The roadmap recommends some draft outcomes, such as number of unemployment claims, percentage of college students that receive a degree or certificate in priority sectors, percentage of employers who agree there is a qualified local candidate for a job posting, and more.

“What stands at the end of all this work, which should make us commit hard, is the quality of life this can give to our people and to those who are coming into industry and trying to figure out, ‘How am I going to make it in Hawaiʻi?’ ” he says. “We knew pre-COVID that 42% of our population was one paycheck away from being houseless. We know today that 59% of our community is in that position as a result of COVID. So how do we provide some confidence that there’s a new pathway for our kids to thrive here?”

Path to recovery

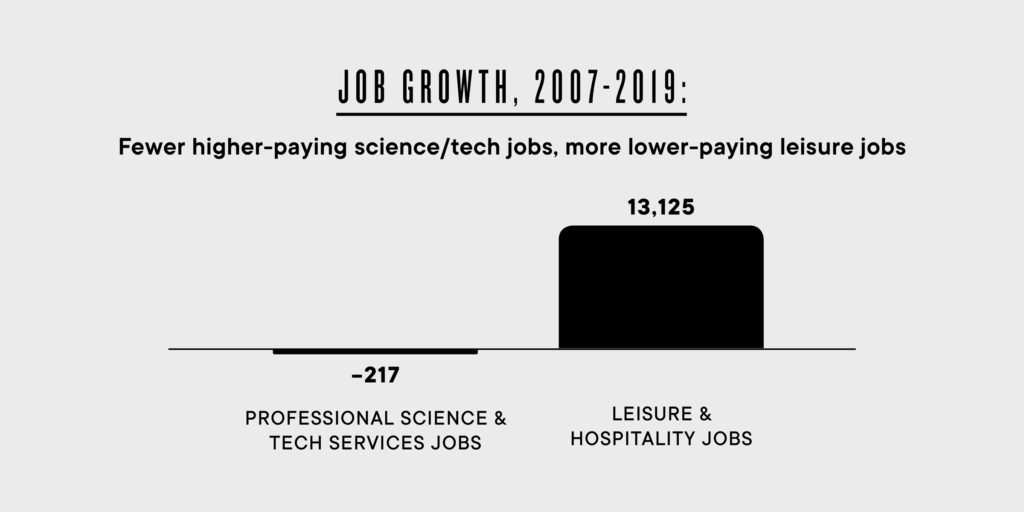

A year ago, Hawaiʻi had one of the lowest unemployment rates in the country. By August, Hawaiʻi had the fourth highest. Part of the problem, according to the Talent Roadmap, is the state had so many workers in low-wage jobs – and a lot of those jobs were in the service sector, which has been hit especially hard by the pandemic.

George describes the solution as a two-sided coin: “It’s really through good jobs for Hawaiʻi’s people,” he says. “You can’t get more people good jobs unless we have a competitive economy with favorable conditions for companies to create new jobs. And you can’t fill those jobs unless we have people qualified to fill them.”

Keala Chambers, VP of Education & Workforce Development, Chamber of Commerce Hawaiʻi

Keala Peters, VP of education and workforce development at the Chamber of Commerce Hawaiʻi, helped develop the roadmap. She points to three ways to help residents acquire the skills they need to excel in in-demand, living-wage jobs: Create more opportunities for workers to quickly learn new skills and to earn credentials; allow for more job shadowing, internships, apprenticeships, on-the-job training and other forms of work-based learning; and generate more collaborations within sectors to address industry-wide challenges and meet shared goals.

The roadmap also suggests strengthening the state’s health care, technology and skilled trades industries – sectors that are considered recession-resilient. These sectors were identified based on an analysis of industry size, the impacts they have on the local economy, the impact of the 2008 recession and insights from stakeholders on how they envision the sectors will drive the state’s economy in the long term. The roadmap also notes that tourism, long Hawaiʻi’s No. 1 industry, can be rebuilt in a way that promotes more sustainable practices and cultural experiences.

The roadmap builds on years of work by K-12, postsecondary and workforce partners to connect more students to high-growth jobs that pay family-sustaining wages, George says. A family sustaining wage is based on the ALICE Household Stability Budgets, which cover the costs of sustaining an economically viable household, plus savings. For a single adult, the hourly wage is $25.49; for a family of four with two kids in childcare, the combined hourly wage for the two adults is $67.33.

Existing examples of collaboration cited in the roadmap include:

- The Hawaiʻi Sector Partnerships, which bring together local industry leaders and other partners to collaborate on sector-specific workforce development initiatives.

- Hawaiʻi P-20 Partnerships for Education’s work-based learning framework, which maps out opportunities so students can gain awareness, explore, prepare and train for careers.

- Efforts by the Chamber of Commerce to identify the credentials most valued by industries.

Related articles: Preparing Teens for Tomorrow | Companies Partner With Schools to Grow Needed Workforce

The roadmap “has some real potential to align around and to take action around,” George says. “Particularly now … when public dollars and private dollars are going to be scarce, we darn well better spend them on things that really matter because there will be fewer dollars spent overall. So let’s spend it on stuff that we know will get people the better skills so they can get better jobs. And it helps our employers, it helps everybody, it helps our communities.”

The Roadmap’s 3 Strategies:

- Rapidly reskill, especially with in-demand credentials

- Expand work-based learning such as job shadowing, internships, apprenticeships and on-the-job training

- Create or nurture more strategies within sectors

Since the Great Recession, Hawaiʻi saw an increase in lower-paying leisure and hospitality jobs, which generally require less education. At the same time, there was a decline in higher-paying science and technology jobs, which require a college education and pay more. | Source: “Hawaiʻi Wages and Household Costs: A Chartbook for Building a Better Economy” by the Hawaiʻi Budget & Policy Center; Current employment statistics from the Hawaiʻi Workforce Infonet.

Gaining new skills

The Talent Roadmap’s strategies can be seen in several programs launched in September to provide training and temporary employment to displaced workers.

The roadmap calls these temporary jobs “lifeboat” jobs because they provide people with immediate income without needing added education or licenses. These lifeboat jobs can enhance existing skills or add new ones that could lead to new jobs or careers.

For example, a laid-off hotel clerk can bring customer service skills to a new role as a stock clerk at a distribution company, George says. That person will learn inventory management and logistics skills, which could set them up for a career as a cargo or freight agent.

This reskilling can also boost new sectors, says Patrick Sullivan, founder and CEO of Oceanit. The technology company is developing a rapid-result coronavirus test and hopes to set up a manufacturing facility in Hawaiʻi. That facility, he says, could help former hotel workers who have good people skills transition into the medical technology industry.

Source: Report called “Filling the Lifeboats – Getting Americans Back to Work in the Pandemic,” May 2020, by Burning Glass Technologies. | Note: Dollar figures are national average annual salaries. Jobs available are nationally.

On-the-job training is key to preparing displaced workers for careers in resilient sectors not dependent on tourism, says Omar Sultan, managing partner at Sultan Ventures and a member of the CHANGE Initiative’s Innovation Economy Committee. He is the architect behind a state program that allows employers to hire up to 650 temporary workers. It’s funded by $10 million in federal CARES Act funding, which covers workers’ wages and health care benefits and some training.

The program has two tracks. One run by the nonprofit Kupu is called the Kupu ʻĀina Corps. It matches participants with jobs in conservation and agriculture. The other, called Aloha Connects Innovation, will match participants with jobs in emerging industries like clean energy, aquaculture and cybersecurity. It’s run by another nonprofit, the Economic Development Alliance of Hawaiʻi.

On Kauaʻi, the Rise to Work temporary employment program has varied positions, including bookkeepers, grant writers, social media managers and laborers. It’s funded with $2.5 million from county CARES Act funds. Some employers use the program to create positions they wouldn’t otherwise be able to offer, says Diana Singh, business innovation coordinator for the county’s Office of Economic Development. Others use it to temporarily bring back jobs they had to cut because of the pandemic.

The hope, she says, is that some positions will turn into longer-term employment, and that, at a minimum, it gives residents a chance to connect with local employers, to learn new skills, and to keep working and advancing in their careers. All of that is important to the mental health of displaced workers, she says. And so is hope: “If all these positions offered was hope – for someone who has been unemployed and has a chance to get back into the community and get back to work – then that’s a success in our eyes.”

ProService Hawaiʻi is providing HR services for the Kaua’i program. Erik DeRyke, VP of client growth and retention, says there are quick benefits beyond just putting people back to work. Temporary employment also provides residents with money that they can spend in their communities, and organizations that provide essential services now have more people who can provide those services.

“So it’s a real kind of a win-win- win scenario,” he says.

The Chamber of Commerce Hawaiʻi launched its Hawaiʻi is Hiring website in July. It’s a one-stop resource for job seekers interested in finding jobs and educational opportunities. Peters says the site had over 100,000 page views and 28,000 users in the eight weeks after it launched, and the education and training section is the second- most visited section on the site.

“This tells me that people recognize that training and education are a good way to spend their time right now,” she says. “We have 25,000 jobs available in Hawaiʻi right now. We have 80,000 unemployed, so we know there’s a gap. So we know this is a valuable time to go get that training.”

Tammi Chun, Interim Associate VP for Academic Affair, UH Community College

Job skills courses provided through the University of Hawaiʻi Community Colleges’ Oʻahu Back to Work program are meant to provide 2,000 displaced Oʻahu residents with initial skills for various fields. And because the courses are free to qualified residents, more residents can attend, says Tammi Chun, UH Community Colleges’ interim associate VP for academic affairs. She cites a HVAC and refrigeration technician class, tuition for which would normally be about $6,000: One hundred people signed up for 16 free spaces.

Leaders of these reskilling and temporary employment programs say these opportunities would not have been possible without federal CARES Act funding. John Leong, CEO of Kupu, says many businesses are downsizing and would not otherwise be able to pay for new employee wages and health care. The Kupu ‘Āina Corps program also provides employers up to $700 per participant to pay for needed equipment and supplies and other onboarding costs.

Hawaiʻi is required to spend its CARES Act money by the end of the year. Some of it will fund the Kupu ‘Āina Corps and Aloha Connects Innovation tracks through Dec. 15, and Leong says Kupu is looking at restructuring its programming and pursuing additional money so it can keep more than 100 Kupu ‘ ina participants beyond December.

Leslie Wilkins, Board of Directors Member, Economic Development Alliance of Hawaiʻi

Leslie Wilkins, a member of the Economic Development Alliance of Hawaiʻi board of directors, says she hopes the Aloha Connects Innovation program will demonstrate how to help displaced workers transition into careers that aren’t reliant on tourism. She is also looking at how participants can connect to additional training and education.

“We really don’t want this to be a one-off and done, just spending the CARES Act money,” she says. “We want this to be an opportunity for career pathway exploration and change, to be able to transition to other pathways and careers that are not visitor-count dependent.”

“We have 25,000 jobs available in Hawaiʻi right now. We have (around) 80,000 unemployed, so we know there’s a gap. So we know this is a valuable time to go get that training.” — Keala Peters, VP of education & workforce development, Chamber of Commerce Hawaiʻi

As the pandemic drags on, many furloughed residents are learning their old jobs are gone for good, and Paul Brewbaker, principal of TZ Economics, says he fears large numbers of local residents will simply give up on finding work.

He says with 80,000 people out of work, Hawaiʻi needs to ramp up its efforts to help residents learn new skills. He agrees with the direction the reskilling programs are headed, but they need “to go way bigger. That’s what I would say. That’s exactly the right focus, it’s just got to be epic.”

Deep Dive recommendation:

Deep Dive recommendation:

Building Hawaiʻi’s Technology Sector

Greater alignment

Wilkins, who is also the president and CEO of the Maui Economic Development Board and chair of the state Workforce Development Council, points to a renewed urgency and understanding that the state’s educational and workforce development systems and employers must work together to build a highly qualified, trained resident workforce.

“We must leverage each other’s resources,” she says. “They cannot be siloed and they cannot run as independent systems.

Peters agrees, and points to one starting point for further collaboration: the chamber’s recent identification of 142 credentials that are highly valued by local industries. Acquiring one or more of these credentials, she says, will allow residents to pursue or advance in occupations that are in demand and that pay a living wage.

Part of the process of identifying the credentials included focus groups and surveys of employers across the state. Secondary and postsecondary partners can now use this information to shape their curricula.

These efforts combined with temporary employment and on-the-job training programs “should result in a workforce that is trained and ready,” she says. “That’s not going to happen overnight, but it’s a progression and it’s all in sync with each other.”

“This type of systemic change isn’t going to happen unless there are leaders and organizations across multiple sectors focused on the same goal, using the same data and taking collective action.” — Micah Kāne, President & CEO, Hawaiʻi Community Foundation

Hawaiʻi was one of eight states to receive an award from the U.S. Department of Education’s Reimagine Workforce Preparation Grant Program. UH received $13.37 million over three years and will work with partners like the state Workforce Development Council, Chaminade University and others to implement parts of the Talent Roadmap, Chun says.

The focus is on helping displaced workers by creating short-term paths, called Hana Career Pathways for occupations in health care, technology and the skilled trades. The name “Hana” comes from the Hawaiian word for “work” and refers to individuals not just having a job but also contributing to their communities, Chun says. The career paths would start with short-term training that could lead to credentials, apprenticeships, degree programs or employment. The idea is that the pathways would allow workers to gain more education and skills and advance in their careers, she says.

Kāne says the coronavirus has helped different sectors hyper focus on diversification. The next steps, he says, are to formalize the roadmap and build closer relationships among the education, government, private, philanthropic and nonprofit communities.

“It cannot be done by any one stakeholder in our community,” he says. “This type of systemic change isn’t going to happen unless there are leaders and organizations across multiple sectors focused on the same goal, using the same data and taking collective action. It’s just not going to happen without it.”